To mark the 70th birthday of Lech Wałęsa in 2013, the Polish Post issued a commemorative stamp. This year’s 80th birthday of the Solidarity leader, an icon of freedom and the overthrow of Soviet domination in Eastern Europe, comes without any state celebration – even the size of a postage stamp.

Wałęsa’s role in the most important event of the second half of the European 20th century is one of the blatant sacrifices laid on the altar of the new version of Polish history being written by the right-wing party who have been ruling Poland for the past eight years (since 2015).

Alleged Secret Service Collaborator

The upcoming state-commissioned revision of the textbook for Polish schoolchildren will include information about the shipbuilder’s collaboration with the communist Security Service in the 1970s, before he assumed his historic position as leader of the Solidarity Trade Union.

It is likely that after the bloody massacre of workers by the communist authorities in Gdańsk in December 1970, young Wałęsa signed papers giving him the alias “Bolek”. However, documents show that for the next six years, he tried to wriggle out of this cooperation. He did this effectively, but “nuances” like Wałęsa’s correction to the decision made during the turmoil, in which many lost their lives, will not be developed in the new textbook.

A Man of Hope

Meanwhile, his legend is one of those about people who are not born but become leaders. Relying on intuition as well as erring, they ultimately make the right decisions, which usually require the wit and courage that others lack.

Lech comes from a small village in the interior of Poland scarred by World War II. His father died as a result of injuries sustained in a German labour camp when Wałęsa was 2 years old (1945). Although life did not formally prepare him to become a global icon, his humble peasant background proved enough to give him the charisma and wisdom of a people’s tribune.

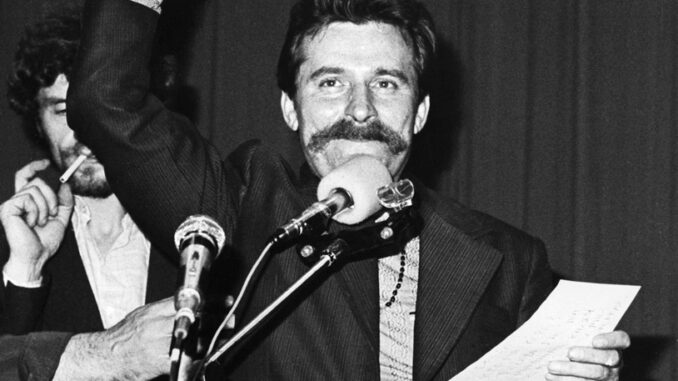

He famously climbed the gates of the Gdańsk shipyard to speak to the striking workers, who opposed the future of a country of shortages, the greyness of Soviet-controlled socialist democracy and the absurdities of social life based on denunciation. In 1980, he led negotiations with the communist authorities. Going against the tide of regime-built mistrust between the working class and the intelligentsia, he opted to accept the support of intellectuals such as Bronisław Geremek and Tadeusz Mazowiecki, future co-founders of sovereign Polish statehood. This rare combination of bold thought, readiness to act, but also considerate restraint led to the social unification of the 10 million spontaneously joining Solidarity members.

The social change thus stimulated – the hope for normalcy in a country plagued by a lack of sovereignty since 1939 – could no longer be contained other than by the arrest of Solidarity leaders and the rollout of tanks on the streets of a country now under martial law (1981-1983). Despite the fear induced by tanks, deadly beatings and shootings at civilians as well as the word “war” that entered everyday usage (martial law in Polish is the “state of war”), the 1980s eventually became a time of hope. Its epitome was Wałęsa. Responsible for a large and constantly harassed family, he did not give in to the security apparatus during the months of internment. It is also worth noting that this year marks the 40th anniversary of his receiving the Nobel Peace Prize (1983, acting on his behalf in Oslo was his wife Danuta), which, along with the election of Karol Wojtyła as Pope, gave Poles faith in the idea of spiritual resistance against abuses of the communist regime.

Failed President?

After 1989, when the impossible became a reality and the authorities sat down to negotiate peacefully with the opposition at the Round Table, Lech was a true icon of peaceful revolution. Speaking in the U.S. Congress, he began with the words “We, the People,” because indeed the Solidarity movement restored agency to individual citizens of a previously authoritarian state. After La Fayette and Churchill, Wałęsa was the third non-head of state invited to address Congress. His speech only sealed Lech’s natural position as a candidate for the first presidency of sovereign Poland.

Alas, what had been Wałęsa’s forte in revolutionary times – spontaneity, decisiveness, improvisation and speaking the language of the people – no longer seemed to work in the times of a regular democracy, also one strongly tormented by economic instability. Some feared his unpredictability as a leader. Others were ashamed of his lack of diplomatic savvy. The Poles were a (too) proud nation who finally managed to achieve something great. At the same time full of complexes against the West, aggravated by their socialist poverty, they did not want to be seen as uncouth. In Lech, many could see themselves in a mirror, and this had a disturbing effect on a society largely devoid of elites in the previous generation (targeted by German-Soviet occupation policies). Also evident here is a certain hunger for success – Wałęsa’s most serious contender for the presidency turned out to be a previously completely unknown, extremely enigmatic but elegant and English-speaking re-emigrant from Canada.

The country was now experiencing the troubles of a young parliamentary democracy mired in the economic reform crisis, which Wałęsa tried to mediate and alleviate with promises. His price to pay for the Poles’ collective complexes and the hardships of the transformation was a narrow defeat in the 1995 re-election. One of the personality traits of “the man who overthrew communism” also exasperated voters, namely his sense of the grandeur of his own achievements, and a conviction of his own rightness. Political maverick, Lech found it difficult to shed the mantle of providential statesman both during and after his presidency.

In 1995, in an extraordinary period of accelerated transformation of the time just lived into History, Wałęsa unexpectedly and unfulfilled left the stage, abandoned along the way by many trusted colleagues from the fractured Solidarity movement. On a personal level – parting with those who followed a more elite (for Poland: left-liberal) political path seems to have hit him the hardest. But over time, it is those who took a right-wing, or rather populist, path that will do him the most harm.

Partly as a personal revenge for ignoring their more radical vision of change, but mainly as a way of constructing their own legend, the entourage of the Kaczyński twin brothers embarked on a crusade to expose the alleged misdeeds of agent Bolek. Effectively stripped of his role as Solidarity leader in the narrative imposed by the Law and Justice Party in schools and the media, Lech today retained his authenticity and ambiguous feature of a perpetually unpolished political gem. Against the backdrop of much more explicit anti-EU backlash of the regional former dissidents (symbolized by Orbán and Kaczyński), he is, however, an unwavering beacon of faith in the EU’s democratic system, increasingly undermined by ruling populists.

A Man with a Moral Compass

Despite his age and as if following an inherent moral compass, Wałęsa is eager to correct any distortions of his political and civic course, which stem in part from his socialisation, which he repeatedly admits. In 1990, he succumbed to antisemitic whispers and suggested distrust to his Jewish colleagues in the opposition. He quickly rectified this mistake and compensated for it with a speech in the Knesset in 1991, in which he became the first Polish president to apologise there and in general for the wrongdoings of Polish majoritarian society towards Jews.

The devout Catholic, who drew political strength from his encounters with John Paul II, has for decades openly spoken out against the most politically influential nationalist wing of the Church in Poland (The Redemptorist running “Radio Maryja”).

Father of a large family, he long defined the role of a wife as primarily the nurturer of the household. Meanwhile, Danuta Wałęsa, not by her own choice and under constant surveillance by the Secret Service, had a 10-million-member trade union office at home, in addition to raising eight children in this small family apartment. When in 2011 she wrote a book describing her actual role in her husband’s (and the country’s) success, Lech gradually began to revise his position and to publicly acknowledge his wife’s merits in both the family and public domains.

Some years ago, he expressed scepticism about LGBT parliamentarians. After a short time and reflection on the issue, he shed this yet another traditional prejudice to express support for the first LGBT candidate for the office of the Polish president. What remains of Wałęsa in Poland is mainly a whole list of his amusing sayings that have not reached an international audience: such as those about the “positive pluses and negative pluses of every situation”; “Break a thermometer and you won’t have a fever” or “I am indeed for and even against”.

Despite the fact that, initiated by Polish liberals, the European Solidarity Centre (2014) was built at the Gdańsk shipyard to pay tribute to this historic site and Andrzej Wajda made an epic film about Lech (2013), it is the fall of the Berlin Wall that today symbolises the transformation of 1989 in Europe. Wałęsa’s brand as a leader of peaceful change or the date of 4 June 1989, which restored free choice to electoral practice in Eastern Europe, do not find consensual recognition among Poles. Wałęsa’s position is stronger outside the country than within it: an electrician from a shipyard with over a hundred of honorary doctorates from all over the world.

The situation is somewhat reminiscent of Gorbachev’s position – respected internationally and marginalised at home. But unlike Gorbachev, whose vision of reforming the USSR failed, Wałęsa’s vision for Poland led the country into NATO and the EU. Despite this fundamental difference, he says: “Nothing can help, nor harm me anymore,” devoid of any illusions about his standing in today’s Poland. Therefore mindless of the etiquette befitting a former president, Lech will not be seen today but wearing the obligatory T-shirt with the word “Constitution” under his jacket, as he supports civic rallies in defence of the tri-partition of power regularly violated by the ruling Law and Justice Party. Unlike his former colleague Kaczyński, Wałęsa has not become the prototype populist. His biggest public dream now is “for Poland to become a true democracy”. Because “when only half of Poles go to the ballot, it’s as if Poland was only 50% democracy”. And it is not the kind of country that Solidarity aspired to when negotiating with General Wojciech Jaruzelski and by extension with Gorbachev.

In both Russia today and Poland, those in power despise the agents of change from the historic year 1989. Putin has long since returned to authoritarianism. And in Poland, Jarosław Kaczyński has from the beginning demanded a more radical solution akin to a new authoritarianism against the old communist one. What is happening in Poland today is a progressive but unsurprising consequence of this political mindset. In the history written by authoritarian leaders, Lech Wałęsa – a man of negotiated compromise whose favourite word was ‘pluralism’ – has no other place than as a discredited communist agent.

In my opinion, we, the readers owe Dr. Lidia Zessin-Jurek a huge “Thank You” for this courageous and expertly written article.

Combining her historical expertise with her writing skills Dr. Zessin-Jurek is able to bring ‘to life’ a brief period (historically speaking) during which one rather obscure man ‘from the working class’ was able to change the course of Polish history with worldwide ramifications.

Again-In my opinion this is a very important article because it serves as a review of the events leading up to Lech Walesa’s rise to power and discusses his short lived ‘rule’ ending in misinformation about him and his accomplishments with the aim to make him a ‘forgotten unimportant man’.

Today the same or similar process is being duplicated by people in regimes who are trying and unfortunately succeeding in re-inventing history.

Case in point: The “Tank Man” who in 1989 held up a tank in Tiamaman’s Square (and was executed shortly afterwards) has been all but erased by Chinese censorship so as the years go by this symbol of defiance in the face of authoritarian rule will be forgotten.

The memories of the 3 ‘Torch’ young men who dramatically and publicly gave their lives to change the regime in Czechoslovakia have been almost lost as the result of the ‘Velvet Divorce’.

As I write this, predictions are that Robert Fico will probably be the leader of Slovakia and no doubt will be an obstacle to NATO and the EU when it comes to unity for Ukraine.

Unfortunately he is joining a growing number of ‘Authoritarian Rulers’ who are re-instituting regimes that we thought would not be possible to reestablish again.

This is not what the Three ‘Torch’ young men, Vaclav Havel and Lech Walesa had in mind and fought for!

The “Western World” is caught in a huge pendulum swing where our basic political democratic values are being attacked by unscrupulous autocrats who wish to rule at all cost and use propaganda, ‘invented history’, intimidation, threats and other tools, methods and means not experienced and seen since just before WWII and practiced during the ‘totalitarian Nazi and Communist eras’ of relatively a few years ago.

This is why I feel that Dr. Lidia Zessin-Jurek’s article exhibits a lot of courage because in it she writes about the actual facts and reviews the historical context in which these events took place in even though the ‘environment’ all around her does not approve of truthful historical facts!