Since the start of 2023, Israelis have engaged in mass protests against proposed legislation that would gut the independence of the country’s judicial system. Demonstrators frame the judicial overhaul as a coup, an overthrow of the democratic norms upon which the state of Israel was founded. On Tel Aviv’s Kaplan Street, where hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gather every Saturday night, crowds chant “De-Mo-Cra-Cy!”; “Democracy” is emblazoned on t-shirts and electronic billboards. Democracy has become more than word; it’s a mantra. But, what does it mean to the demonstrators?

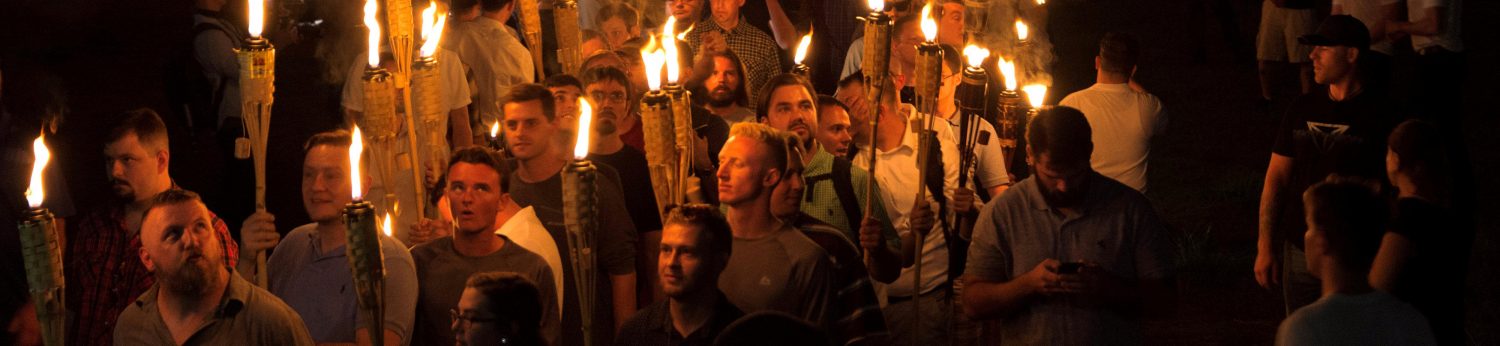

The celebration of democracy is an assertion of ethnic solidarity. With few exceptions, the demonstrators are Jews. The demonstrations’ core consists of secular Jews of Ashkenazic descent, the eastern and central European Jews who formed the country’s founding elite and continue to dominate the judiciary, academia, and the media. There are also Orthodox Jews, Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin, and Jews on the political right-wing. There are some Jewish settlers from the Occupied Territories. At the Tel Aviv protests, there is an area for protest against the occupation, which includes Palestinians. There is even a Palestinian flag. But this is the exception, not the norm.

The pro-democracy movement’s familial, intimate spirit is derived from its Jewishness. It is a reminder that, throughout its history, Israel has been a procedural democracy for all its citizens, but a liberal democracy for only its Jewish ones. Israel’s courts and legislature have declared Israel to be a “Jewish and democratic,” but it is, in fact, a Jewish-democratic state: an ethnic democracy that privileges a national majority. Beyond the now-invisible Green Line—the armistice lines fixed at the end of the 1948 War—millions of Palestinians have, since 1967, lived under one form or another of Israeli occupation, beyond the penumbra of Israeli democracy.

Israel’s founding declaration did not mention the word “democracy.” It pledged equal treatment regardless of “religion, race, or sex,” but not nationality. The declaration called upon “Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to preserve peace and participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions.” But these words neither impeded the forced exile of 750,000 Palestinians nor fostered their return after the war. After the war, when Israel absorbed over a million new immigrants and built new communities on former Palestinian villages, there was little desire to include the Palestinian refugees in the Israeli state. In the Israel of the 1950s and 1960s, there were no perceived contradictions between the state’s claim to democracy, the forced removal of 60% of Palestine’s Arab inhabitants in 1948, military rule over those Arabs who remained, and the confiscation of millions of acres of Arab-owned land.

This conception remained fixed in Israeli collective memory for generations to come. Fear of Arabs outside of Israel’s borders blended with suspicion of and condescension toward Arab citizens. Israeli public support for retaining and settling the territories conquered in 1967 had more to do with security than messianic zealotry. These feelings were reinforced by Palestinian terrorism, which killed some 1500 Israeli Jews between the outbreak of the First Intifadah in 1987 and Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza in 2005. Protests by Palestinian citizens of Israel against land expropriation and discrimination were interpreted as an extension of terrorism. In this atmosphere, most Israeli Jews still saw few contradictions between full democracy for Jews, second-class status for Arabs within Israel, and occupation of those in the West Bank and Gaza.

In the 1990s, the Oslo peace process was not aimed at recognizing Palestinian human rights so much as separating Israel from the occupied territories to preserve the state’s Jewish character. The main concern of the Israeli Center and Left was the future of a democracy where Jews would remain not only a majority, but also the dominant party.

The principle of Israel as both Jewish and democratic was enshrined in Israeli legislation and jurisprudence in the mid 1980s. The principle was strengthened by the introduction in 1992 and 1994 of two additions to the body of quasi-constitutional legislation known in Israel as Basic Laws. The new Basic Laws (Human Dignity and Liberty and Freedom of Occupation) addressed neither the second-class status of Israel’s Arab citizens nor the occupation of millions of rightless and disenfranchised Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. But the laws blazed a trail towards the recognition of Arab claims on equality within the state. In 2000, for example, the Israeli Supreme Court invoked them when it decided in favor of an Arab family’s right to acquire a home in a community hitherto restricted to Jews.

However, in 2018, another Basic Law was enacted in order to halt this jurisprudential course in its tracks and to counter what was thought to be a Palestinian “demographic threat.” The law officially described Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People. Circumscribing democracy within Jewishness, and eliminating the putative parallel relationship between the two, the law formally declared Israel to be what the sociologist Sammy Smooha calls an ethnic democracy.1 Centrist and leftist parties opposed this Basic Law, and its passage elicited dismay among many Israelis. But the consternation which greeted the Basic Law did not come close to the explosive combination of frustration, fear, and panic that has energized massive protests since early 2023. What changed between then and now?

The difference is that now the pillars of Israel as an ethnic democracy are under attack. A key element of the judicial overhaul is granting the legislature the ability to overrule the Supreme Court when the court rejects legislation as unconstitutional. A bare majority in the Knesset could rewrite and effectively abrogate previous Basic Laws. For example, it could gut the Basic Law on Human Dignity and Liberty, which would threaten Israeli citizens’ rights to intimacy, privacy, and protection from arbitrary police action.

Secular Israeli Jews feel threatened by the increasingly hawkish and religious Knesset. A third of the Knesset’s current members are Orthodox, and some of its most energetic legislators have agendas to inculcate the Israeli educational system and civil society with a militant Judaic nationalism. The more that the proposed overhaul weakens the judiciary and strengthens the legislature, the more likely Israel is to change from a democracy that privileges Jews over Arabs into a tyranny of the Jewish majority over the Jewish minority.

Last but not least, the current government has successfully mobilized longstanding resentments by Jews of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) origin against the so-called “First Israel” of Eastern European origin. Although in its first decades the young state of Israel discriminated against Jewish immigrants from Arab lands, it fostered an ideal of Jewish unity. In contrast, today’s Israeli government employs the language of Jewishness to set sub-ethnicities against one other. Nonetheless, this strife remains intra-, not inter-, communal. It takes place within the extended family of the Jewish people.

This Jewish-centered self-perception is held by those protesting against the judicial overhaul as well as those promoting it. The protesters are brave, concerned, and patriotic citizens with progressive social and political values. But the waving of Israeli flags and the ritualistic invocation of Israel’s founding declaration at the demonstrations are signs of nostalgia for the élan of Israel’s founding. Nostalgia is a powerful yet, literally, regressive emotion. The protest movement has, for the most part, been reluctant to acknowledge openly that the assault against Israel as an ethnic democracy has been enabled by the state’s longstanding failure to function as a liberal democracy.

Derek Penslar is the William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History at Harvard University

Leave a Reply