From time to time, the New Fascism Syllabus will be hosting roundtable discussions centered around emerging historiographical contributions, questions, or issues. Featuring some of the leading voices on these various debates, these contributions in this series are intended to serve as an Open Access window onto new directions in historical analysis on topics ranging from Fascism, right-wing populism, and authoritarianism in the 20th century. In this roundtable discussion, scholars of German Queer Studies explore the significant methodological contributions made by Jennifer Evans’ The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship after Fascism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023).

This roundtable discussion was co-curated by Anna Hájková, Brian J Griffith, and Sophie Wunderlich.

From time to time, the New Fascism Syllabus will be hosting roundtable discussions centered around emerging historiographical contributions, questions, or issues. Featuring some of the leading voices on these various debates, these contributions in this series are intended to serve as an Open Access window onto new directions in historical analysis on topics ranging from Fascism, right-wing populism, and authoritarianism in the 20th century. In this roundtable discussion, scholars of German Queer Studies explore the significant methodological contributions made by Jennifer Evans’ The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship after Fascism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023).

This roundtable discussion was co-curated by Anna Hájková, Brian J Griffith, and Sophie Wunderlich.

The Queer Art of History: Kinship After Fascism narrates the lives of LGBTQ+ people through the practice of queer kinship following the Second World War to contemporary German history. Jennifer V. Evans draws from contemporary works in Black feminism, queer of color discourse, queer theory, and trans* studies to move beyond narratives of identity towards solidarity across intersectional differences. Evans embodies this solidarity throughout this monograph by extending this “experience of together-in-difference” (Evans, 185), folding in numerous histories of race, gender, and sexuality to that of everyday life in Germany. Extraordinarily, these histories do not fall under cohesive narratives of queer excellence but instead provide complicated and at times difficult tales of our queer kin past.

As stated by Evans, “queer kinship is not flawless, but it does hold the potential to destabilize monocultural minoritarianism and recollect the role of race, class, and gender nonconformity within the queer past” (Evans, 185). In using queer kinship as a methodology, queer history is presented as a practice in which heteronormative visions of society are negated in the promise of alternative visions of a queer future. Queer Art of History cements the notion that there is not one universal kinship but an infinite array of lived queerness. Despite the tumultuous setting of postwar Berlin as a city split by power, identity and trauma, Evans highlights the manners in which people continued to seek out one another. Kinship is lived by sex workers of all genders and sexualities as they stood ‘cheek to cheek’ on solicitation zones or it could be found inside West Berlin revues where French, Spanish, North African and Black German performers of varying ages and identities performed alongside their white German counterparts (chapters 1 & 3). Within these spaces, queer folk created micro-areas in which they were able to live queer potentialities, able to experience liberties and freedoms not yet acquired or granted by governments and society.

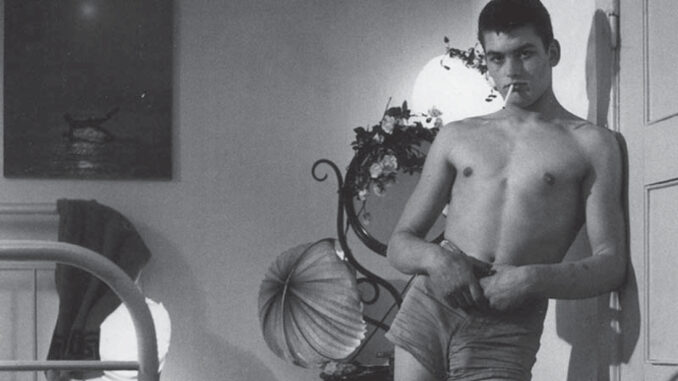

However, during my first reading, kinship introduced an unpleasant tension. This sensation was magnified in the second chapter of the book where Evans discusses the photographer, Herbert Tobias. Initially a fashion photographer, Tobias gained notoriety for his erotic photography, predominately his depictions of sex work during the 1950s. Within this chapter, Evans introduces instances of intergenerational connections as sites of kinship through intimacy, mutuality, and eroticism. The images produced of rent-boys illustrate a period in which intergenerational intimacy and desire took place. But these encounters were not only experienced by Tobias but were also marketed to a general gay public. In the magazine him (later renamed him applaus), Tobias recounted titillating stories of these transgressions and published the images of his adolescent conquests. Evans remarks how Tobias’s work contained “important revisions of postwar imaginaries,” despite being interpreted as “fundamentally at odds with how we think about good, consensual relations today,” (Evans, 54). Evans makes an excellent point; we in the current cannot uphold Tobias to our contemporary standards of consent nor demonize him for living within an Edelmanian queer negativity. The inclusion of the Manfred Schubert photograph within histories of kinship is not meant to obscure their coercive and unbalanced dynamics but to also view them as pieces of queer fantasy and imaginings. She calls us to view these photos within their context and asks not to place our contemporary values onto these pieces.

Despite understanding Evans’s argument, I still felt uncomfortable viewing these photos. I spoke to two queer friends about my unease viewing the Tobias photographs and showed them a photo of Manfred Schubert. They too felt uncomfortable. We noted that the uncertain consent, age, and happenings outside the image emphasized the illicitness of its setting. Manfred is illustrated noticeably young in skintight shorts, shirtless and barefoot with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. He leans against the door frame in masculine contrapposto evocative of James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. The unkempt bed beside Manfred and his challenging gaze creates a sexually charged tension between sitter, photographer, and viewer. The messy bed and half-naked state sublimely confirming that a transaction had occurred and that our interlocking eyes suggest another might occur again.

Questions of appropriateness were raised when discussing Manfred with my friends. We all agreed that our discomfort with the image stemmed not from the implications of sex work and its transactions but rather on the age of the worker. One friend, the younger of us three, felt that these images were documentation of the harmful stereotypes of queer desire. As the more financially stable adult within this transaction, Tobias and his work was interpreted as pedophilic and whose audience equally partook in these manipulative fantasies. They did not care if Manfred agreed to be photographed. In trusting his older, more experienced partner, Manfred could not truly and fully consent to both sex and the sharing of his story. This friend was reluctant to continue engaging with the image or with Tobias’s history, deeming him irredeemable and not worthy of extending the hand of kinship.

Their immediate discomfort with the Manfred Schubert photograph is reminiscent of ongoing discussion by younger millennials and Gen Z regarding depictions of sex in popular media. Recent articles have been dubbing these stances as a part of ‘puriteen’ culture often attributing a rise in conservative approaches to sex, alcohol, and drug use to the overall generational decline in sexual activity. This can seem at odds as we are cited to be more Left-leaning and liberal than previous generations often supporting LGBTQ+ rights, gender equality, access to abortion, and sex-positivity. But what is considered sex-positive takes on a different meaning. In a Slate article from 2022, Sarah Marshall of the You’re Wrong About podcast stated that “the previous iterations of sex positivity were very focused on the pro-sex aspect, but not necessarily the power dynamics that are inherent in pretty much any sexual interaction.” In other words, sex-positivity and depictions of sex are required to be positive representations where all actors are held to contemporary standards of appropriateness.

With this definition, there is no room for neutrality. In fact, Evans actively describes these stances as practiced forms of bad kinship in that the “inegalitarianism and coercion has the unfortunate effect of negating the possibility of agency…” (Evans, 65). For instance, looking at these photographs through a purely, puriteen lens we rob Manfred of his power. We would automatically classify him as a victim of Tobias rather than regarding a potential mutual desire. His relationship with Tobias was an active choice in which he knowingly capitalized on his youth and power over his older client. Evans confirms this, stating that “while the spectator explores his body with their eyes, Manfred’s stance and counterstare invite this action. He is both the subject and object of desire” (Evans, 74). It is no longer about Tobias’s influence over him but the reaffirmation of power. Us, the viewer, are looking at him on his terms. For the newer generation, the choice to be photographed in moments of vulnerability, sexual or not, rests upon the subject rather than the photographer. Is this not our definition of sex-positivity?

In victimizing Manfred, we also negate the experiences of younger queer teens who see themselves within the photograph. This was expressed by my other friend, who in their youth used websites like Omegle to chat and interact with queer adults. Omegle, which launched 2009, is a website that connects strangers worldwide through chatroom and video chats without the need to register. Its ‘18 and older’ policy rarely stood in the way of us younger millennials as we went ahead and chatted without parental permission. For some of us, websites like these were the only way to interact with other queer people. Unable to ‘come out’ and unsure of who to share our sexuality with, the internet was a way to explore our developing sexualities. My friend shared that they had actively spoken with older queerfolk in these chatrooms, often seeking their attention and advice. These folks shared their own experiences and transferred knowledge that would have been rather hard to find in the early 2000s. Even now this friend does not see these interactions as coercive, nor do they feel like a victim. To them, the photograph of Manfred reflected these kinds of sensations. They represented desires of adolescent fantasy in which they wanted to be seen and wanted to be wanted.

But what about Tobias? Most of our conversation had centered around the subject of the images but had left its creator in its side-lines. One friend did not wish to acknowledge Tobias while the other was unsure of their feelings. Our initial preconceptions towards Tobias were coated in our own generational relationship with eroticism and sex. Fantasy and the sharing of fantasy has always been accessible to people of my generation and younger. I, like many, grew up with unrestricted internet and our formative years were spent exchanging sexual and violent content between friends and classmates. Not to mention, we were also exposed to popular media’s obsessions with teenage sex through movies like 1995’s Kids, 2003’s Thirteen as well as through television shows like late 2000’s series Skins and more recently in HBO’s Euphoria. While we initially liked being represented in media tackling ‘adult’ issues and scenarios, as we grew older, we realized that the audience was not only made-up of fellow teens but adults as well. This realization can be uncomfortable. We grew up witnessing teenage representations as the objects of tabooed desire by the adults in charge of us and saw them hold countdowns for popular child stars turning the ‘legal’ age as recently as 2022. It is in this reality in which we assess Tobias. His role in cementing canons of underaged, transgressive aesthetics echoed to other forms of media. Tobias is reminiscent of the unjust power dynamics expressed by the adults around us. It is tough to admire the aesthetic establishments of his work when living in its consequence.

While our sentiments are valid, this was not the point of Evans’s argument. Once more, kinship is not inherently positive. To practice kinship is not to regard Tobias as a positive or even a negative character but instead to see his contribution to queer history itself: “Tobias combined select elements of turn-of-the-century gay iconography and pictorialism with a fascination with class, race, youth, friendship, and brotherhood to stage a transgressive multivalent gay subjectivity as the cornerstone of queer kinship and identity” (Evans, 82). Tobias’s photography documented different elements of queer desire—one that was often understood as low-brow or seedy—transformed into said gay canon. Tobias did not hide his young love fantasy in Caravaggesque hodgepodge but was among the first to present for what it was. We are not being asked to dispel our discomfort but are challenged to instead include figures and moments of discomfort in our queer history whether we like it or not.

What Evans cements throughout Queer Art of Kinship is kinship as a form of inclusivity. While our contemporary vocabulary associates this with positive representations, true inclusivity permits narratives from the margins. I still feel like there is a divide between the practice of kinship and its application into generational discourse. In my attempts to practice kinship, I am having to actively mitigate my generational biases and re-examine why my initial reactions can be antithetical. Afterall, our values change with the passage of time as will our stances on consent, sex, and intergenerational relationships. I still feel odd when viewing Manfred Shubert, but I will extend my hand to Manfred and Tobias through togetherness and difference.

Paola Medina-Gonzalez is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Warwick and co-host of the podcast Theoryrish

Sources

Evans, Jennifer V. Queer Art of History: Kinship After Fascism, Durham, Duke University Press, 2023.

Hampton, Rachelle and Sarah Marshall, “What Everyone Gets Wrong About Gen Z and the Sex It’s Allegedly Not Having,” Slate (April 30, 2022).

Lehmiller, Justin J., “Generation Z is Missing Out on the Benefits of Sex,” Psychology Today (September 8, 2022).

Leave a Reply