A series of “fully genocidal” articles recently laid out a plan to erase Ukraine from the map. A plan for genocide against Ukraine, published by the Russian state-run media agency RIA Novosti, has attracted condemnation from around the world, but has been underplayed in the United States (US). Author Timofei Sergeitsev, a Russian political consultant, argues that the political and military elite of Ukraine “must be liquidated; their re-education is impossible” and that the “accomplices” of the regime will be put to “forced labor to restore the destroyed infrastructure.”

Ukrainian history, culture, and language will be forbidden, or, as he puts it, “the further denazification of this bulk of the population will take the form of re-education through ideological repressions (suppression) of Nazi paradigms and a harsh censorship not only in the political sphere but also in the sphere of culture and education.” This will require the “establishment of permanent denazification institutions for a period of 25 years.” Furthermore, “the name ‘Ukraine’ cannot be kept.” Sergeitsev has been a columnist with RIA Novosti since 2014, whose official status means the article could only have appeared with the approval of the highest authorities. More recently, Sergeitsev again published an article re-confirming these points.

Sergeitsev is a member of the Moscow Methodological Circle, a group of philosophers and political consultants who are connected to important members of Vladimir Putin’s administration, such as Putin’s First Deputy Chief of Staff Sergei Kiriyenko. The Methodologists develop media campaigns for important government projects. These include the Russian World project, dedicating to culturally incorporating the global Russian diaspora that has become a revanchist project. Methodologists also worked on the campaign for Novorossiya, which preceded the creation of the breakaway republics in Ukraine’s east. Sergeitsev worked for pro-Russian Ukrainian politicians as part of this struggle for Russian influence in Ukraine.

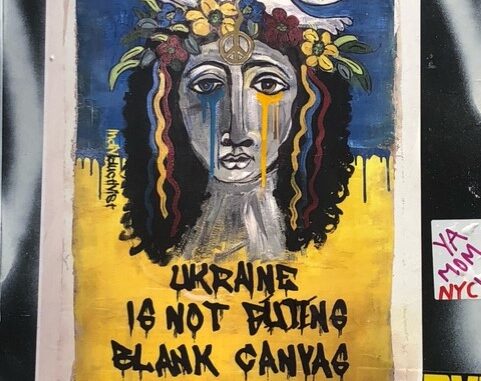

His article sees Ukraine as nothing but empty territory—one that will have its name removed and be reshaped completely by Russia’s genocidal plans. This vision of territory is an integral part of plans for genocide.

According to the April 4 article, Ukraine will be divided into two. Eastern Ukraine will be carved up into peoples’ republics and all members of the democratically-elected Ukrainian state will be forbidden to take part in politics. Organs of government and militia units will be formed with direct Russian oversight. As Sergeitsev notes, “perhaps this will require a permanent Russian military presence in the territory.”

Western Ukraine will become what Sergeitsev calls “the Catholic province.” This overlaps with the areas earlier under Habsburg and, later, Polish rule. Although technically independent, this rump Ukraine will not be allowed to use any Ukrainian symbols. According to Sergeitsev, the “guarantee of the preservation of this obsolete Ukraine in a neutral state must be the threat of an immediate continuation of the military operation in case of non-compliance.” Significantly, only that part of Ukraine that had not been historically part of Russia is given the possibility of separate existence.

The larger implications and historical roots of Sergeitsev’s article can be illuminated by my work, which, for the past two decades, has focused on Russian ideas of territory. There are two eras of Russian spatial thought that are especially important here. The first extends from the late eighteenth century to 1991 and shows that post-Soviet Russia inherited a long-standing sense of territory as vacant and malleable. The second, and more important, covers the post-1991 era, when the power of the Russian state to define the world became part of an information war.

Sergeitsev reflects the view of Ukrainian territory as space that can be reshaped at the will of the Russian state. He embraces the use of genocide to achieve this goal. Its publication in such a mainstream and widely-read outlet shows that the Russian government does not consider it necessary to hide such plans. Since the late eighteenth century, Russian high culture portrayed its own provinces, including most of the country outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg, as without meaning, which could only be bestowed by the center. Historical and literary sources, such as descriptions of provinces under Catherine the Great and works by Nikolai Gogol (Mykola Hohol, in Ukrainian) and Anton Chekhov show that both Russian state and society saw the country’s regions as empty and open to the capital to define and remake as desired. In what would become Ukraine, a very different approach emerged from the 1820s that celebrated regional differences, which would later form the basis of a true national culture.

During the Soviet era, the belief that territory could be transformed by the state was an integral part of Marxism-Leninism, as massive dams, canals, and other industrializing projects reshaped the land. In Soviet Ukraine, a man-made famine under Stalin in 1932 and 1933 known as the Holodomor resulted in the deaths of roughly 3.9 million Ukrainians and replaced villages with collective farms.

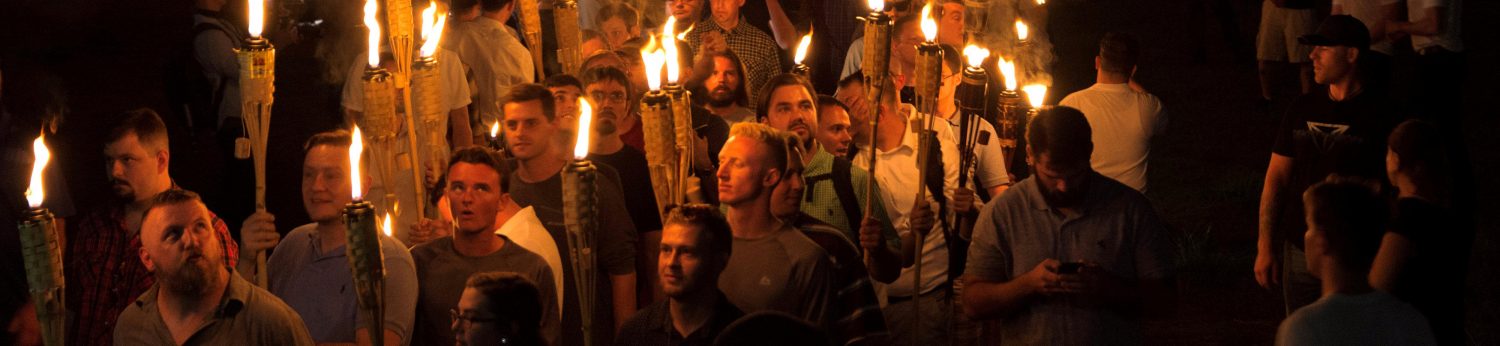

In the 1990s, this enduring spatial tradition, which could have developed in a variety of ways, was shaped by a new vision of information war. Influenced by Russian philosopher Alexander Zinoviev, Methodologists believe that the individual, like a computer, can be programmed and reprogrammed. By the 2010s, Methodologists played a leading role in many of the state-run campaigns and Olga Zinovieva, the widow of the philosopher, articulated a concept of information war that called for the Russian state to define itself and its neighbors, particularly Ukraine, through propaganda. The Sergeitsev article is part of a larger effort to define Ukraine so it can then be erased and filled with new content.

The larger consequences of this are significant. The official publication of a plan for genocide by a state which has already started carrying it out must be met with the strongest possible condemnation and action by the West. After the Holocaust, many people said they didn’t know what was happening. Now we know because a plan has been published. We have no excuse not to act.

Thanks for this article! I didn’t know about the Moscow Methodological Circle. Chilling!