This article was republished on the New Fascism Syllabus with the permission of the author and the original publisher, zeitgeschichte|online

As much as war is about armed military conflict, it is also fundamentally about mass displacement, broken lives, and lost futures. This simple truth has become way too obvious in large parts of Poland, where providing food, clothes and shelter to strangers, and collecting donations to help refugees from neighboring Ukraine have become common practices among “ordinary” people. With over three million (as of March 16) Ukrainians fleeing war, Poland became a hub for more than half of them, often as a first stop en route to their families and friends across Europe.

Much of the efforts of this grassroots mass mobilization to help those escaping their war-torn country falls on the shoulders of various parts of society, including individual activists and non-activists as well as civil society organizations. Volunteers hook up on social media and with the help of other informal channels, weaving a complex web of support including private apartments, informal transportation, and food distribution. In Poland, going to protests, chanting anti-Putin slogans, watching the images of intensifying attacks on Ukrainian towns and of women with children escaping war in horror go hand in hand with collective acts of solidarity and kindness. Within a couple of days, virtually all my close friends in Warsaw were hosting refugees, preparing dozens of sandwiches for new arrivals, offering them a warm embrace, and so on. Both the intensity and scale of the Russian invasion of Ukraine make this experience strange, terrifying, overwhelming, and too close to home.

Initiatives of the Minority Communities

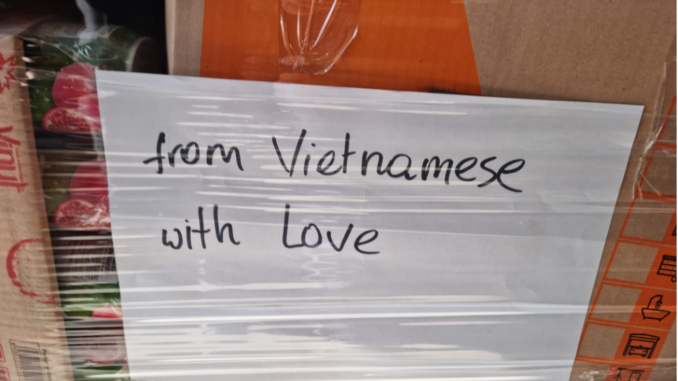

What is perhaps less visible in this civil society mobilization and its media coverage1 are the efforts of migrant and minority communities that do their share in offering relief to those fleeing from Ukraine. For instance, members of the Vietnamese community, one of the oldest and largest non-European communities in Poland whose roots go back to the 1950s, organized a food tent at the remote border crossing station in Zosin-Uściłóg. For over a week, Phan Châu Thành and his wife Hà Thị Huệ Chi, who organized the tent and many other forms of help, co-ordinated the Vietnamese, Polish, and Ukrainian volunteers and offered Vietnamese cháo (congee), sandwiches, and hot beverages to refugees. Tôn Vân Anh, a known Vietnamese activist, was one of the first ones to organize a transportation for Vietnamese minorities fleeing Ukraine. Launched by first- and second-generation migrants from Vietnam, the initiative also involved collecting money and providing daily necessities as well as housing in the Vietnamese Pagoda and the Asian wholesale trade center in Wólka Kosowska to the Vietnamese seeking refuge.2 In that sense, it did not differ much from other initiatives. On March 10, Ngô Văn Tưởng, who had come to Poland as a student before 1989, launched the informal initiative “Gorące obiady” (hot lunches) that involved Vietnamese restaurants delivering around 60 warm lunches daily to refugees in the old office complex Atrium that is taken care of by the city of Warsaw. This form of social activation builds on the experience of Vietnamese activists during the pandemic when immigrant-owned restaurants began delivering free meals to medical staff battling the pandemic in Warsaw and beyond.

As carriers of the “invisible wounds” caused by war and decolonization, the Vietnamese know all too well the brutalizing dynamic and psychological impact of a seemingly endless armed conflict. The older generations of migrants from Vietnam also personally know many Ukrainians with whom they shared the ebb and flow of the 1990s as migrant workers running small restaurants and working at outdoors markets. As their example shows, the experience of bloody decolonization can map onto that of the regime transition in Eastern Europe. Vietnamese-owned food services are often trapped in boxes of cheap-eats.3 But for many older generations of immigrants from Vietnam, entering the food business, even if they did it for lack of other options, was a gate to a somewhat stable income and eventually upward class mobility. Another branch is that of import and export business (usually a wholesale one) that goes back to the early 1990s when the Vietnamese traded in the new outdoor markets that were mushrooming throughout Poland. It is precisely this blending of perceived war-time commonalities, shared first-hand experiences of turbulent post-socialism, and the concrete skillsets of first-generation urban migrants working in the food industry and transnational trade business that propels the Vietnamese community in Poland to help refugees from Ukraine today.

Another example of grassroots activism comes from the African-Polish community that has become active in supporting Black people and people of African descent fleeing Ukraine. A central role in this movement of support is played by an alliance of six organizations: Black is Polish, Centrum Intersekcjonalnej Sprawiedliwości w Polsce (Center for Intersectional Justice in Poland), Stowarzyszenie Rodzin Wieloetnicznych Family Voices (Association of Multiethnic Families Family Voices), Pracownia Antyrasistowska (Anti-racism Workshop), Fundacja na rzecz Różnorodności Społecznej (Foundation for Social Diversity or FRS), and new visions. One of the people behind the efforts to help all refugees is Margaret Amaka Ohia-Nowak, a well-known activist committed to protecting the rights of the African-Polish community and spreading awareness around racism. Support offered by the African-Polish activists includes free rides from the border, access to temporary accommodation, legal services, counselling, and general assistance for those willing to settle in Poland. This initiative is as much about reacting to the atrocities of war as it is about countering the disparities in treatment of various groups of refugees at the Polish-Ukrainian border. According to international media coverage and eyewitness accounts,4 people of presumably African, South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Middle Eastern background fleeing Ukraine had to wait significantly longer when attempting to cross into Poland, at times had less access to help on the Polish side, and were attacked in at least one case (on March 1, in the Polish town of Przemyśl, four Indian students who just arrived from Ukraine were physically assaulted by right-wing hooligans). Against this backdrop, it quickly became clear that pre-existing infrastructures and local networks of activists with an experience in fighting for the fair treatment of Black and Brown people in Poland was able to respond to an emerging need arising from the specific wartime hardships faced by groups that are racialized and othered.

The Polish Roma community has been assisting Ukrainian Roma people who, at times, also faced racist treatment while evacuating from Ukraine. A scholar and activist, Joanna Talewicz not only helps Ukrainian and Ukrainian Roma refugees but also fights anti-Roma biases in the media coverage of the war. Talewicz is a co-founder of Fundacja w stronę dialogu (Foundation for Dialog) that is collecting donations for fleeing Roma people and provides all types of support similar to the ones offered by other NGOs and activist circles. One of the major challenges the foundation addresses is the prevailing and deeply rooted racialized stereotype of Roma people that presents them as criminal and lazy, which is part of a larger culture of anti-Roma racism. These powerful and harmful representations of Roma people often make it harder for them to find housing and transportation. According to Talewicz, at least 100 Ukrainian Roma people arrive daily in Warsaw (as of March 12) and stay at the facilities organized by the city; also there racial tensions prevail. Like other refugees from Ukraine, the arriving Roma people see Ukraine as their home—their friends, husbands, brothers, and sons fight in the Ukrainian army. They also lost their home and want to return to Ukraine. Just as African-Polish activists do, Polish Roma activists point to the fact that the wartime experience of Roma people and other racialized communities fleeing Ukraine is layered with biases. In that sense, their experience of wartime violence and forced displacement has an intersectional dimension to it. (Without doubt, Ukrainian women and children seeking refuge also experience forms of intersectional violence that disproportionately impact women such as trafficking, rape, and other challenges related to gender that are often overlooked.5) Activists helping Roma refugees feel less supported as they, unlike Vietnamese and African-Polish activists, have no embassy and few institutions to turn to for help. As these cases exemplify, the grassroots response to the humanitarian crisis caused by Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, also mobilizes and consolidates migrant and minority communities in Poland. Combining specific historical experiences, unique skillsets, and the embedded knowledge of a particular community in this specific region together with a more wide-ranging sense of universal solidarity and compassion, they identify and expose exclusionary dynamics as much as they help to bridge existing divides.

The Underbelly of Help

Despite the massive outpouring of self-organized support for refugees from Ukraine, several major challenges are looming large over this large-scale mobilization. What were mostly discussions taking place at the fringes just a few days ago now become more visible in the mainstream media. How long can such grassroots forms of help that build on collective acts of kindness and solidarity last? With more and more volunteers facing the enduring stress of working in a logistic chaos and shrinking resources there seems to be growing unease about the limited involvement of state institutions and the lack of a sustainable and systemic response.6 Some activists who have been active at the Polish-Belarussian border in order to address the desperate situation of asylum-seekers trapped in the woods there for the last months express frustration with the wide gulf between the treatment of refugees at the Polish-Belarussian border and those coming from Ukraine. Just a few hundred kilometers north of the Polish-Ukrainian border, refugees were and still are being pushed back onto the Belarussian side by the Polish Border Guard and experience violence from the Belarussian Border Guard. Families with children were and still are freezing in the woods, not knowing if and when they will be able to safely cross into Poland. Anna Alboth, an activist from Grupa Granica (Border Group), recalls how little understanding and support they received from the Polish state and other European societies in helping refugees at the Belarussian border in comparison to the current, immediate, and massive wave of emotional and material support for Ukrainians.7

Broadening the Scope of Care and Aid

Everyone would probably agree that instead of pitting one group against the other, comparing their levels of suffering, and their raisons d’être, it is important to ask: Who counts as a refugee and which refugees count? Although answering such a seemingly innocuous question might be painful, we need to ask it in order to prevent reproducing exclusions and marginalizations in the very act of solidarity and helping. To inquire whether racist hierarchies or a sense of cultural proximity might play a role in shaping and limiting aid and solidarity touches on a thorny and difficult topic, but instead of hindering spontaneous and conscious support for those in need it should broaden its scope. There is little doubt that years and years of anti-refugee discourse propagated by the conservative part of the Polish authorities have tapped into, as well as amplified, racial sentiments. The effects are now becoming visible even within this enormous and impressive wave of solidarity.

At the same time, racism might not be the sole factor in explaining divergent reactions. Many commentators from “the West” forget or do not fully realize that the cultural and geographical proximity of Poland and Ukraine is woven deeply into a difficult but intimate shared past. This historically rooted and culturally encoded closeness magnifies a sense of collective responsibility for the Ukrainian society that has become a victim of an imperial state that is perceived as a common enemy as it has posed an existential and real threat to Poland as well. Against this background, the violence targeting Ukrainian society is opening up old wounds while creating new ones. In that sense, the mass support for Ukrainian refugees in Poland cannot be simply boiled down to arbitrary favoritism. Although collective burnout, limited resources, and the uneven redistribution of help provide the dark underbelly of the current, and impressive mass mobilization across Poland, the point is not to erase the tremendous support offered by Polish society and its humanitarian as well as political value. Rather, the point is to realize that even grassroots initiatives with the best intentions can go hand in hand with forms of disparate treatment and exclusion that are as deeply rooted as the sense of connection and commitment that underlies the mobilization.

Migrant and minority mobilizations in Poland highlight that reactions to current crises can rarely be understood in exclusive reference to “the here and now.” The support coming from the migrant and minority communities build on a semi-organized practices of solidarity and help that are often rooted in prior experiences, activities, and discourses. African-Polish and Roma activists do not merely offer an ad hoc support for refugees—they also continue to battle discrimination and systemic challenges. The Vietnamese do not only focus on providing food to refugees—they appropriate and turn around the stereotypes and roles in which they are pigeonholed.

Ultimately, those in need of support are civilians trying to flee under circumstances that are hard or even impossible to imagine for most of us: exhausted women carrying even more exhausted children while waiting for hours or days to reach a safe place, broken families, destroyed cities and villages, environmental destruction, circumstances that blend extraordinary agency with total vulnerability, and dependence on others. As Viet Thanh Nguyen, himself a former refugee, once wrote: “To become a refugee is to know, inevitably, that the past is not only marked by the passage of time, but by loss—the loss of loved ones, of countries, of identities, of selves.”8 It is also this knowledge of loss and remarkable agency that motivates many to help those who are at risk of losing everything today.

Thuc Linh Nguyen Vu is a Researcher at the Research Center for the History of Transformations at the University of Vienna

If you wish to support refugees in Poland, consider donating via the following organizations:

- “Support Black and Brown people fleeing war in Ukraine” (FundRazr)

- Platforma Roma-Poland-Ukraine – pomoc dla romskich i nie-romskich uchodźców i uchodźczyń – znajdź nas na FB! (Fundacja w Stronę Dialogu)

- Fundacja Ocalenie

- The Ukrainian House in Warsaw

Notes

- While the Polish media do not leave the incidents of uneven and racist treatment unchecked, they pay less attention to the migrant and minority activism providing aid to the refugees.

- As of March 18, more and more Vietnamese communities from Europe (e.g Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands) join the efforts of the Polish Vietnamese activists turning this instance of migrant activism into a transnational one.

- Think of the German “Imbiss” or the Polish “iść do/na Chińczyka” (to go to the Chinese/to have some Chinese food) as examples for describing cheap food. While “Imbiss” refers to a cheap and quick meal, and might have more of a working-class undertone to it, the informal ways of referring to Vietnamese food in Polish have an essentializing quality to them; as if Asia was a big country named China.

- For instance, see: Monika Pronczuk and Ruth Mclean, “Africans Say Ukrainian Authorities Hindered Them From Fleeing,” The New York Times, March 1, 2022, retrieved on March 17, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/01/world/europe/ukraine-refugee-discrimination.html; Krzysztof Boczek, “Ocean pomocy, krople rasizmu – co działo się w dniu, kiedy przez Medykę przechodzili nie-Ukraińcy,” okopress.com, March 17, 2022, retrieved on March 17, 2022, https://oko.press/ocean-pomocy-krople-rasizmu-co-dzialo-sie-w-dniu-kiedy-przez-medyke-przechodzili-nie-ukraincy/; Andrej Popoviciu, “Ukraine’s Roma refugees recount discrimination en route to safety,” aljazeera.com, March 7, 2022, retrieved on March 17, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/7/ukraines-roma-refugees-recount-discrimination-on-route-to-safety/.

- A number of Polish NGOs and activists have been ringing the alarm bells about refugee women being exposed to the risk of sex trafficking on the Polish side, see: https://rzeszow.wyborcza.pl/rzeszow/7,34962,28170333,sutenerzy-na-granicy-z-ukraina-podkarpacka-policja-zaprzecza.html; on the suspicion of Russian soldiers sexually assaulting Ukrainian women, seen Natalia Waloch, wysokieobcasy.pl, March 19, 2022, https://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,163229,28236206,zolnierka-znad-granicy-potrzebna-pilna-pomoc-dla-ukrain.html; retrieved on March 19, 2022.

- See, e.g. https://tvn24.pl/tvnwarszawa/najnowsze/warszawa-wolontariuszka-o-punkcie-recepcyjnym-na-torwarze-po-wczorajszym-apelu-sytuacja-sie-poprawia-5630908; Piotr Halicki, “Dramat na Torwarze. Szefowa wolontariuszy: żarty się skończyły,” onet.pl, March 9, 2022, https://wiadomosci.onet.pl/warszawa/dramat-na-torwarze-emocjonalny-apel-szefowej-wolontariuszy-jestesmy-na-skraju/3vr95xw, retrieved March 19, 2022.

- Anna Alboth, interview, Gazeta Wyborcza, March 8, 2022, retrieved on March 17, 2022, https://wyborcza.pl/magazyn/7,124059,28196613,czym-rozni-sie-syryjskie-dziecko-uciekajace-przed-bombami-putina.html

- Viet Thanh Nguyen, et al. The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives (New York: Abrams Press, 2018), 22.

Leave a Reply