Like the other contributors to this blog over the past week and many other regional experts from around the world, as a historian of the Soviet Union I am sickened watching the unprovoked and illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine happen in real time. I am not an expert on Ukrainian history and politics like many colleagues and folks from Ukraine whose voices are so important right now. Apart from doing my best to distill what is happening for my students, I wasn’t sure I had further analysis to contribute.

But then I began to see the videos and images of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy circulate – giving a new speech, red-eyed and exhausted but resolute; confirming in a shaky group cell-phone video that he and the men of his cabinet were alive and fighting in Kyiv; insisting via Twitter that he would not accept an evacuation offer from the U.S. government. Social media lit up: “He’s got balls of steel!” “Don’t fuck with Ukrainian men!” “Look at Grandpa Putin beside the hero Zelenskyy!” At that point I thought, as a historian of gender and culture in the Soviet Union and in particular of martial masculinity during and after the Second World War, perhaps I do have something to say about all this.

If that sentence provoked a sigh and you are thinking: this is not the main issue, people are dying – I get it. Nothing is more important right now than stopping the violence, getting refugees to safety, and supporting the people of Ukraine in any way we can. There will be time to indulge in gender analysis later, surely. But I would argue that this is a significant issue right now, because narratives are beginning to form that could have staying power, affecting Ukrainian and Russian societies long-term: what did you, as a man, do during the war? How did you fight back? How did you protect “your” women and children? Were you a coward, or were you a real man?

Questions like that, both direct and more subtle, snaked their way through Soviet culture and society after the Second World War, a catastrophic four years that led to upwards of 27 million dead in the USSR, including soldiers, civilians, and many in between from Russia, Ukraine, and the other Soviet republics. The surviving cohort, the frontoviki – veterans of the front – were able to wring badly needed social services from Stalin, who feared their capacity for armed revolt, and became exalted figures in Soviet culture. That reverence largely did not extend to women veterans, despite the unparalleled contribution to the war effort by Soviet women (again, featuring Russians, Ukrainians, and many others). For a variety of reasons, including some embarrassment in the government and military that they had needed to rely on women to fight at all, service was remasculinized, or recategorized as the purview of men, from the late 1940s on.

Today, I see three main areas developing on the issue of gender and war: first, masculinity narratives about Putin; second, about Zelenskyy; and third, about the everyman, which includes both teenage Russian conscripts and Ukrainian civilians, who are renegotiating new categories of martial masculinity as this war grinds on.

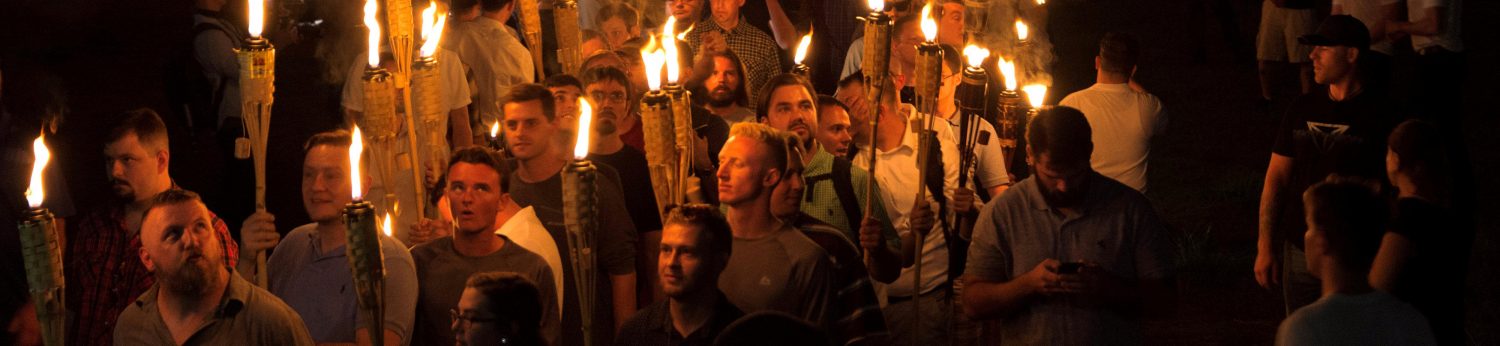

First, Putin’s masculinity has long been a topic of interest for both armchair commenters and academic gender scholars. The iconic photograph of him shirtless atop a horse has circulated widely and contributed to his reputation for many years in the West as a tough guy, a renegade in world affairs, a man who epitomized what sociologist Raewyn Connell called “hegemonic masculinity” more than two decades ago. That term described a preeminent but constantly shifting form of masculinity defined primarily by a.) dominance over women and b.) militant heterosexuality, usually demonstrated through anxieties about sex between men.

Historians of gender and diplomacy, such as Kristin Hoganson, Mrinalini Sinha, and many more have argued for more than twenty years that anxieties about the masculinized fitness of a nation, as well as the leader’s personal understanding and performance of his own masculine identity, has had deadly real-world consequences in war and colonialism. The future answers to the question all of us want to know right now – “Why has Putin done this?” – will be multicausal and complex, but gender anxieties should not be dismissed. His performance of hegemonic masculinity thus far has relied on perpetuating real-world harm against women (through the decriminalization of domestic violence, for example) and queer folks (through the ban on information about queerness as well as the state violence against gay men in particular). A full understanding of Putin’s motivations will require asking further questions about his perception of Zelenskyy as a less virile man and Ukraine as a “soft” country in gendered terms, open to and actively courting “western penetration.”

Next, where does Zelenskyy fit into a discussion of martial masculinity? First, let us spare a genuine moment of admiration for his remarkable bravery and crucial leadership in the past week. As I mull over these academic questions, I honestly have no desire to malign him. But his masculinized identity, still very much in flux, has been fascinating to watch. Much has been made of his previous job as an entertainer; as of this writing, Twitter is awash in old video clips of everything from his dance performances (including some in drag) to his work as the wholesome voice of Paddington Bear in the Ukrainian version of that film. Juxtaposed with these images are others of Zelenskyy in a simple pullover sweater, exhausted but resolute. I cannot begin to imagine what he is going through, fearing for his own life while showing strong leadership for the Ukrainian people and the watching world.

The image of the jokester or buffoon becoming a “real man” through military service has a longer history in Soviet culture. After the demobilization of the late 1940s, the Soviet military faced a huge problem convincing the next generation of boys and young men to complete their required military service. Despite the nominal peace of the time and the coercive powers of the state, internal reports consistently appeared in the Ministry of Defence and the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) that young men were finding all sorts of ways out of their military service – everything from playing up physical challenges to hiding at the village level from conscription authorities.

My research into this resistance (to what was relatively benign peacetime service) found that military and governmental authorities turned to the cultural front to try to convince more young men that serving was a properly masculine endeavour. Too young to have served in the war, this new generation, authorities assumed, would jump at the chance to prove themselves in service and become part of the gendered power structure in Soviet society that put military masculinity at the top.

This cultural offensive included the production of films like Maxim Perepelitsa and The Soldier Ivan Brovkin (both from 1955). Both feature a young, pre-service hero who was something of a clown in his Ukrainian village, always pulling pranks and making jokes, enjoying his easy life devoid of responsibility, purpose, or discipline. Army service was portrayed in both films as a privilege reserved for the most deserving men. “A man like that doesn’t belong in the army! He will spoil the honour of a soldier!” bellowed an elderly villager as the young Maxim Perepelitsa insisted he could change his jokester ways if he were only permitted to enlist (the film obscured any coercion). Another villager countered, “Let him go, for in the army he will become a man.”

Films like these produced by Moscow in the 1950s encouraged young men to complete their martial transformation to elite masculinity through service. But the message behind their Ukrainian settings and main characters was more subtle: Ukrainian villagers in particular had fought not only the Nazi invader but the Soviet government in Moscow, and that war did not end in 1945. Partisan fighters continued to challenge Soviet control of Ukraine long after the war officially ended, and those men were not innocent buffoons who would ultimately be transformed into loyal Soviet soldiers like Maxim or Ivan.

That brings me to a third area: the transformation of both Russian and Ukrainian men into soldiers, at least in the emerging narratives of the war so far. Russia’s reliance on a conscript army of the young and reluctant also has a much longer history. Reports emerging from Ukraine right now of bewildered 18-year-old Russian conscripts bursting into tears, asking to call their mothers, or not understanding the war or their role in it, all contribute to a particular narrative that strips them of their access to martial masculinity and its presumed hegemony in society. The brutality of the invasion is lessened if we highlight the youth and inexperience of the men on the frontlines. It also draws on the history of powerful mothers’ groups in the Soviet Union, especially the perestroika-era Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers that organized against conscription to the war in Afghanistan. We should watch how these tropes and labels play out, and particularly how Russian soldiers, and women at home, assert their own voices. Soldiers denied full access to the privileges of military masculinity – even in rumour and myth – might well decide to take it for themselves.

Finally, what to make of gendered narratives already emerging about the Ukrainian resistance fighters? What strikes me in these early days is the commitment among Ukrainian commenters to preserving a plurality of masculinities among this new crop of emergency soldiers. For example, in order to militarize, Ukrainian masculinity need not shed other categories, like fatherhood, compassion, class or region, and so on. We could have seen a different narrative emerge, endorsing the regular Ukrainian army and asking everyone else to stand down as civilians, thereby preserving the privileges of martial masculinity for the elite, armed few. Instead, we hear of members of the Ukrainian diaspora abroad coming back to fight; fathers tearfully leaving their families to take up arms; community patrols adopting puppies from the street; older Ukrainian volunteers taking the confused Russian teenagers under their wing and helping them call home; women honouring the World War II era service of their grandmothers to do what they can against this invasion. That plurality is significant, and it speaks to a burgeoning form of martial masculinity that is not predicated on misogyny and homophobia like Putin’s.

While the current focus has to be on helping as many people in Ukraine as possible to find food, medicine, and safety, the coming weeks and months will see analysts try to piece together why Putin has initiated this violent invasion of a peaceful country, and how Ukrainians mobilized martial categories of identity to fight back. I hope scholars of gender and power will find space in that discussion.

Erica L. Fraser is an Associate Professor in the Department of History at Carleton University and the author of Military Masculinity and Postwar Recovery in the Soviet Union

References & Further Reading

Connell, R.W. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Costigliola, Frank. “‘Unceasing Pressure for Penetration’: Gender, Pathology, and Emotion in George Kennan’s Formation of the Cold War.” Journal of American History 83, no. 4 (1997): 1309-39.

Edele, Mark. Soviet Veterans of World War II: A Popular Movement in an Authoritarian Society, 1941-1991. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Eichler, Maya. Militarizing Men: Gender, Conscription, and War in Post-Soviet Russia. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Hoganson, Kristin L. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Krylova, Anna. Soviet Women in Combat: A History of Violence on the Eastern Front. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Novitskaya, Alexandra. “Patriotism, Sentiment, and Male Hysteria: Putin’s Masculinity Politics and the Persecution of Non-Heterosexual Russians.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 12, no 3-4 (2017): 302-18.

Randall, Amy. “Soviet and Russian Masculinities: Rethinking Soviet Fatherhood after Stalin and Renewing Virility in the Russian Nation under Putin.” Journal of Modern History 92, no. 4 (Dec. 2020): 859-98.

Sinha, Mrinalini. Colonial Masculinity: The Manly Englishman and the Effeminate Bengali in the Late Nineteenth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995.

Spackman, Barbara. Fascist Virilities: Rhetoric, Ideology, and Social Fantasy in Italy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Sperling, Valerie. Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Wood, Elizabeth A. “Hypermasculinity as a Scenario of Power: Vladimir Putin’s Iconic Rule, 1999-2008.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 18, no. 3 (2016): 329-50.

Leave a Reply