At this time, my heart is with colleagues in Ukraine suffering under the conditions of invasion. As all other Holocaust scholars, my sleep has been disturbed by many nightmares over the years. But now I have nightmares in the daytime. I keep thinking of Kharkiv, of its people, parks, and architectural monuments devastated by Russian rockets. I keep thinking of the Holocaust scholars I know or met there. I have been constantly on the verge of tears for a week now.

There was no scholarship at all on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union. It was simply not allowed. And for years after the collapse of the USSR, the inertia of the Soviet way of thinking dominated independent Ukraine’s academy so that there was scant improvement in the situation.

Then about ten years ago, a young man from Kharkiv, Yuri Radchenko, reached out to me by email with the draft of a text about the role of Kharkiv’s civil administration in the Holocaust. I was gobsmacked. It was an excellent piece, researched on the basis of local archives. I had a bit of money from a grant, so I hired an experienced editor to fix the English of his text. He sent it off to a leading journal in the field, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, where it was published in 2013. That was the beginning of our relationship.

We met thereafter from time to time at Holocaust conferences and research centers. I was amazed by the fellow. He is such a polyglot. Aside from his native Russian and Ukrainian, he has learned English, German, and Hebrew, and probably other languages. I suspect he has been learning a Turkic language recently, in order to pursue his new research project about the Karaites during the Shoah.

In 2017 he received a fellowship from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies in Edmonton, Alberta, where I live. My family hosted him for several months. He was then in his late twenties or early thirties. He’s quite tall, maybe 6’ 4”, and my family nicknamed him “The Yeti.” We all grew exceedingly fond of him.

After he became head of the Center for Interethnic Relations Research in Eastern Europe at V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, he was able to invite me to Kharkiv for a seminar on the Holocaust and other mass killings on Ukrainian territory during World War II. This was in April 2018. He and his colleague Artem Kharchenko , another Holocaust scholar, took me on a tour of what was, until recently, a beautiful city.

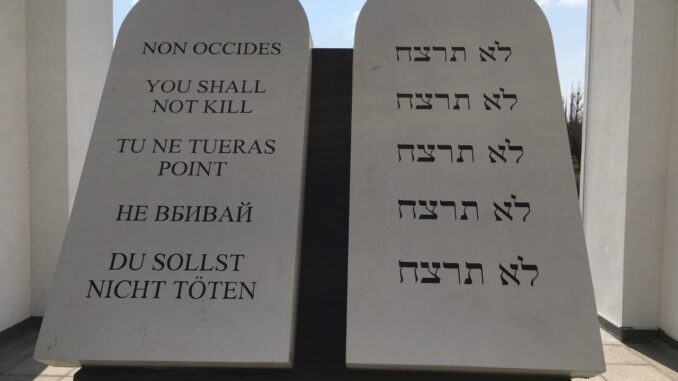

We also went to Drobytsky Yar on the outskirts of the city. This is a huge ravine in which up to twenty thousand victims of the Nazis are buried, primarily Jews. Now there is a memorial center at the site. One of the sculptures there is in the form of the tablets with the ten commandments. But instead of ten different commandments, it only contains the fifth commandment, “You shall not kill,” in five different languages on the left and five times in Hebrew on the right.

At the seminar itself, which was also attended by the well known Polish Canadian researcher Jan Grabowski, I met young, up-and-coming Holocaust scholars from different parts of Ukraine. I particularly remember Roman Shliakhtych from Kryvyi Rih, in central Ukraine. He has been researching the role of the collaborationist police in the Holocaust on the basis of local records. I also saw Andriy Usach, whom I had already known from Lviv. He gave a short but hard-hitting paper about sources for understanding the mindset of local collaborationist perpetrators. I returned to Canada much heartened by what I had seen and heard of the new Holocaust scholarship.

Yuri and I have continued to collaborate intellectually. In fact, just a few days before Russia invaded Ukraine, he was advising the Russian translator of my recent book on the Holocaust on questions of terminology.

I can’t mention all the Holocaust scholars I fear for, but I have to say something about Marta Havryshko of Lviv. I met her in 2017 on a trip to Ukraine. At that time she was working on sexuality and sexual violence in Ukraine during World War II and during the Ukrainian nationalist insurgency and Soviet counterinsurgency that followed it. She had a knack for interviewing the old women who managed to survive the horrifying 1940s in Ukraine. She brought them little presents and met them on the common ground of women’s experience. They opened up to her in a way that any scholar would envy.

Then she turned to work on sexual violence during the Holocaust. She has also done stunning new work on women as perpetrators. She has, since I met her, had fellowships from the major Holocaust research institutions, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

While Yuri is jovial, Marta is intense. I understand this: she has had to put up with a lot of discrimination in her academic workplaces because of her feminist and critical positions. Recently, however, she landed a new academic position as director of the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research at the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center in Kyiv. She emailed me just before this past Christmas to ask if I would help her with a program she is initiating. The Center wants to give grants to teachers offering courses on the Holocaust. She requested my help in vetting applications and giving the applicants feedback on their syllabi, to which I agreed.

In informing me about the Center’s plans, Marta was very proud of the Crystal Wall of Crying designed by Marina Abramovic and erected at the site of the Nazis’ mass murder of Kyiv’s Jewish population. I wonder if it’s still standing after Russian artillery has attacked Babi Yar. I don’t think we will be able to give out those grants for a long time now.

I have been able to find out what is happening to all of the scholars mentioned. Yuri is internally displaced, in the countryside outside Kharkiv. Artem is in the city with his family. On 27 February, Kharchenko published a short piece for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz to say that he’s taking up arms in defence of his homeland. Roman remains in Kryvyi Rih. He wrote to me: “We are holding on, our city is still quiet. But the situation is changing every hour.” Andriy was in Estonia when war broke out, but made his way back to Lviv, “not without adventures.” He also wrote that “we are doing all we can to stand firm.” Marta wrote that she is in Lviv, which so far is not being bombed. “Everything looks threatening, and I am thinking of leaving the country with our son. The poor child cannot sleep, has gotten sick from stress, and is asking when the war will be over. In the meantime we are volunteering, helping the army, refugees, and our relatives who have fled from Kyiv.”

I am worried about the fate of the blossoming Holocaust scholarship in Ukraine if Russian forces take over the country. And of course, I worry very much about the personal safety of my dear colleagues as Putin pretends to “denazify” Ukraine with tanks and artillery.

Leave a Reply