Casteel, Sarah Phillips. Black Lives Under Nazism: Making History Visible in Literature and Art. New York: Columbia University Press, 2024.

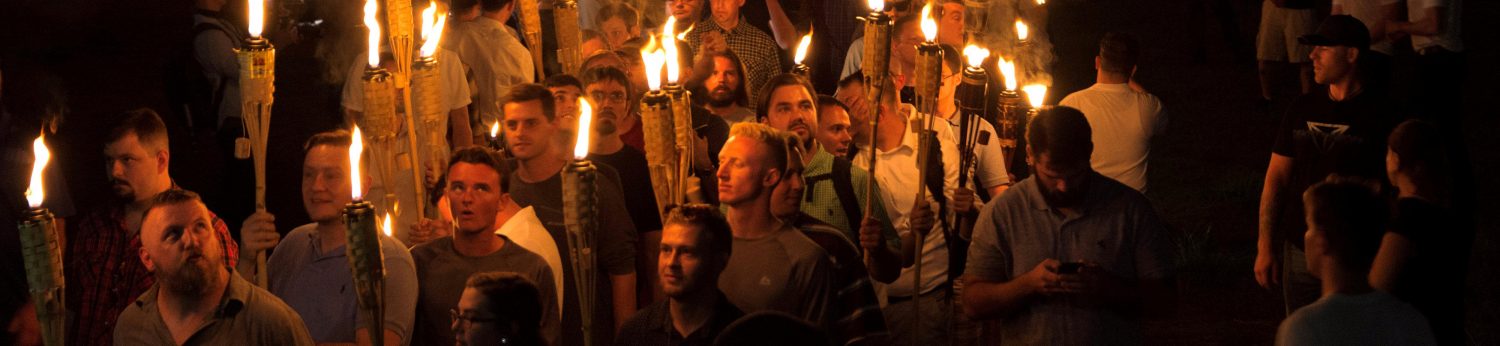

Black Lives Under Nazism by Sarah Phillips Casteel draws attention to the largely unrecognized field of African diasporic literature and visual art that addresses the Black experience in interwar and wartime Europe. Casteel’s purpose is not to interrogate historical facts but, rather, to help the reader understand how this art affects historical memory. She refers to this art as an agent of black wartime memory, rather than as merely a vehicle. Casteel believes studying this topic is essential due to the imperative of challenging the systematic erasure of black historical perspectives following World War II (WWII).

A common argument that Casteel makes throughout her study is that the Holocaust cannot be viewed as a monolithic narrative. She argues that the perspective of blacks who suffered under Nazism is much different than the experience of other ethnic groups, such as the Jews, and therefore should be examined outside of the narrow lens used to categorize Holocaust victims. She also argues that many black victims of the Holocaust were not merely victims of the Third Reich but were able to maintain their agency through various artistic forms, which Casteel examines throughout the study.

Casteel begins by focusing on the visual diary of Josef Nassy, a Surinamese artist of African, European, and Sephardic Jewish ancestry who the Germans incarcerated in an internment camp due to his feigned American citizenship. Nassy’s work emphasizes the everyday lives of prisoners in internment camps, who, unlike concentration camp inmates, were not occupied with forced labor and thus struggled to find ways to remain productive in a restricted, dull environment (pp. 37-8). Casteel observes that Nassy best captures the psychological atmosphere of the internment camp by portraying his fellow prisoners (p. 39). Following WWII, the definition of the Holocaust became almost exclusively centered around the suffering of Jews, and the Nassy Collection only continued to be included in Holocaust art exhibitions due to his Jewish heritage. This collection is now owned and displayed by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, which classifies it as internment art separate from concentration camp art (pp. 56-7). “As the Nassy Collection illustrates, visual art produced in the camps chronicles dimensions of the history of civilian internment during World War II that textual accounts fail to register” (p. 59). The use of visual diaries to reveal a scarcely documented historical event is superb.

In the second chapter, Casteel focuses on the memoirs of three Afro-European men. After narrating the experiences of these three men, Casteel argues the term “Holocaust” can be problematic since it homogenizes the experiences of prisoners of different backgrounds, ethnicities, and faiths into one monolithic narrative (p. 66). Casteel argues that memoirs “by virtue of its democratizing force, simultaneously challenges the invisibilization of African diaspora wartime experience” (p. 67). Casteel shifts her focus to further explaining the literary mode used by these men, which she calls bildungsroman. This narrative form “tracks the protagonist’s youthful hardships and explores the relationship between human development and sociocultural context” (p. 72). Casteel concludes by observing these memoirists “reclaim the self-determination and agency that had been denied them by the Nazi regime” (p. 88).

In Chapter 3, Casteel critiques the jazz fiction novels of John Williams and Esi Edugyan. Their works differ in style: “Williams adopts the solitary voice of a troubled bluesman while Edugyan embraces jazz’s ‘ensemble sound’” (p. 98). Casteel argues that both works are essential since they “uncover material intersections between African and Jewish diasporic histories that have been perceived as separate” (p. 99). Casteel emphasizes the importance of historical fiction in drawing attention and research to a field of history in which testimonies remain largely unrecorded and whose testimonial objects remain largely uncollected (p. 102). Edugyan’s novel is especially interesting since it highlights the creative collaboration between black and Jewish musicians in the development of jazz, which the Nazis considered “Jewish-Hottentot frivolity” To underscore this connection, Louis Armstrong appears as a character and is depicted as having an affinity with Jewish culture (p. 117). The novel also heavily focuses on testimonial objects, such as the band’s records, to help tell the story (p. 122).

In the fourth chapter, Casteel explores the life and career of Valaida Snow, an African American jazz trumpeter who defied gender norms since jazz trumpeting was male-dominated (p. 132). Following an incident with law enforcement in German-occupied Denmark, Snow claimed to have been imprisoned and brutalized in a concentration camp. However, her narrative was questioned, and according to Mark Miller, a jazz historian, she likely made the story up to gain attention and revive her career. Casteel mentions the many musical dramas and short stories that narrate Snow’s life (p. 143). Some of these portrayals do not hide the controversial elements of Snow’s life, including her deceitful character (p. 145). However, other portrayals attempt to justify “Snow’s biographical revisionism as necessary to her survival as a Black female performer in the early and mid-twentieth century” (p. 146). In conclusion, Casteel argues that regardless of whether Snow was honest about her imprisonment in a Nazi concentration camp, her story is still important since it draws attention to other black artists who the Germans imprisoned (p. 153).

In Chapter 5, Casteel explores how invisible history can be analyzed and visualized. To understand this phenomenon, she examines the life and career of Maud Sulter, a Scottish Ghanaian artist. Her photomontage, Syrcus, is designed to challenge the invisible barriers which have prevented academic and public research into the suffering of blacks under Nazism. She mainly accomplishes this by juxtaposing images of African carvings onto European scenic backgrounds (p. 156). Unlike the other artists mentioned, Sulter rejects intimate portraiture and realism in her work, instead preferring to disrupt the more normal art form (p. 159). Sulter was bothered by the invisibility of black art in Europe, especially the art of black women. Casteel concludes by reiterating the importance of Sultur’s work in using unrealistic, disruptive imagery to challenge historical preconceptions (p. 185).

In the final chapter, Casteel focuses on the career of Oxana Chi, a German Nigerian dancer who created a visual artwork called Durch Garten Tanzen. This artwork focuses on the life of Chi’s friend Tatjana Barbakoff, who perished at Auschwitz, and seeks not merely to tell a story rooted in history but to connect the past, present, and future, drawing attention to the effects of xenophobic violence throughout history (pp. 187-192).

Casteel’s work provides insight into a narrow topic of the Holocaust, which scholars have largely overlooked. The visual diaries, memoirs, and other forms through which the stories of black victims of Nazism are conveyed validate Casteel’s argument that the experiences of this demographic do not fit neatly within the monolithic Holocaust victim narrative. However, Casteel could have stated her argument more firmly, tied it in with each chapter and bolstered it with a concluding chapter, which this study ultimately lacks. Also, Casteel might have substituted the controversial case study of Valaida Snow with another lesser-known jazz trumpeter whose authenticity as a victim of Nazism has not been disputed by scholars.

Although this reviewer agrees with the basic premise that there is no single, monolithic narrative for all of the ethnic groups that suffered in the Holocaust, scholars of this topic need to make a more robust and more detailed argument as to why that was the case. To do anything less would be a disservice to the memory of the Holocaust victims.

Leave a Reply