From time to time, the New Fascism Syllabus will be hosting roundtable discussions centered around emerging historiographical contributions, questions, or issues. Featuring some of the leading voices on these various debates, these contributions in this series are intended to serve as an Open Access window onto new directions in historical analysis on topics ranging from Fascism, right-wing populism, and authoritarianism in the 20th century. In this roundtable discussion, scholars of German Queer Studies explore the significant methodological contributions made by Jennifer Evans’ The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship after Fascism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023).

This roundtable discussion was co-curated by Anna Hájková, Brian J Griffith, and Sophie Wunderlich.

From time to time, the New Fascism Syllabus will be hosting roundtable discussions centered around emerging historiographical contributions, questions, or issues. Featuring some of the leading voices on these various debates, these contributions in this series are intended to serve as an Open Access window onto new directions in historical analysis on topics ranging from Fascism, right-wing populism, and authoritarianism in the 20th century. In this roundtable discussion, scholars of German Queer Studies explore the significant methodological contributions made by Jennifer Evans’ The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship after Fascism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023).

This roundtable discussion was co-curated by Anna Hájková, Brian J Griffith, and Sophie Wunderlich.

It is a pleasure and privilege to read and reflect on such a rich, urgent, and ambitious book. Jennifer Evans’ The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship after Fascism aims to fundamentally recalibrate our orientation towards the queer and trans* past. The book’s centre of attention is Germany, but through its central analytic of queer kinship, the impact of The Queer Art of History will reverberate far beyond the confines of this national context. It is essential reading for anyone interested in understanding how dynamics of gender, sexuality, and race have shaped post-war history—and what this means for doing historical work.

Let me start, then, with kinship. It offers at once a roadmap for historical research as well as an analytic, which allows Evans to foreground the “coalitions, attachments, hookups, solidarities of choice and necessity” between people who have felt and desired queerly (certainly including but expressly not limited to those who have claimed a minoritized queer, gay, lesbian, or trans* identity). These coalitions and attachments are political, emotional—and often sexual. Indeed, Evans’ understanding of kinship is erotically charged. This is a historian who puts front and centre the “messiness of sexual transgression” (p. 2) sometimes elided in those accounts which consciously or unconsciously ‘smooth over’ the unruly contours of queer life and passions. Instead of politely directing the reader’s gaze to more reputable matters, Evans celebrates the “radical potential of the erotic.” This focus is especially clear in the most evocative chapter of the book: a stunning analysis of the erotic photography of Herbert Tobias, originating in the 1950s homophile press but subsequently serialised in 1970s gay magazines.

Refusing to relegate Tobias’ street photography to the realm only of the exploitative, Evans shows the centrality of cross-class and intergenerational dynamics to these images. She also invites us to reflect on what these photos stir in us today, leaving us to dwell on the disconnect between the ‘acceptable’ twenty-first century queer subject and the reality of the queer historical record. When Evans encourages us to “view the queer past more suspiciously,” (p. 18) this strikes me not only as a call to avoid the search for innocent victims and/or valiant heroes, but also as a reminder to remain vigilant about our own practice, whether in the sense of navigating the pull of the identarian present, or in censoring our own work. Which of us can say that we have never worried about the reaction of our audience(s) to the more salacious, the less ‘respectable’ aspects of our archival findings or our journeys through queer print culture? We would do well to follow Evans’ call and to recognise the potential of a historical practice “oriented around relationships of affiliation and encounter—intellectual, physical, libidinous, emotional” (p. 19). Here, the physical and the libidinal must not be written out.

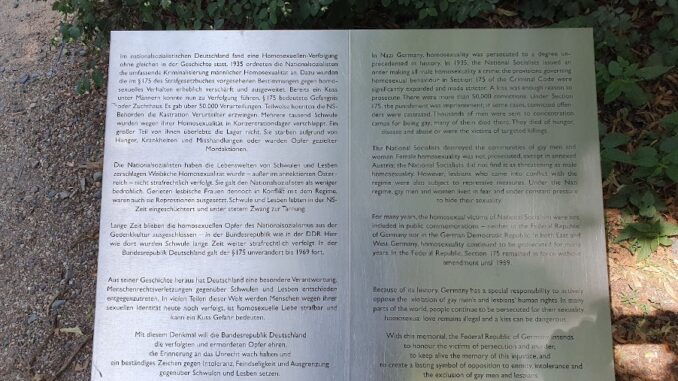

In this second chapter of the book, as in many others, Evans builds on and critically reflects on her earlier work. Just as she refuses to iron out the inconsistencies and permissive edges of the historical actors whom she analyses, she applies the same logic to her own historical practice. Evans admits where her view on a historical subject was too narrow, or when she missed an analytic opportunity to dig deeper, or when a conference she participated in—bringing into view our academic kinship networks—was permeated by whiteness. In chapter five, Evans re-evaluates the controversies over the 2008 unveiling of the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism (situated in the Tiergarten in Central Berlin, directly opposite the better known and much larger Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe). Evans has published on this important marker of queer commemoration for a decade. In this intervention, she explodes and excoriates the limited vision of some historians (often, but not always, gay male historians) who are reluctant to consider the ways in which the Nazi regime’s persecution of queer people went beyond homosexual men.

She also looks afresh at the monument’s signage (easily missed by the passing tourist), whose homonationalist overtones were less clear to her when first publishing on this topic. This signage positions present-day human rights abuses against gays and lesbians as outside Germany, or committed by non-Germans. In this vein, Evans explores how the LSVD (the Lesben- und Schwulenverband in Deutschland, or Lesbian and Gay Federation in Germany), the country’s largest queer organisation, has been complicit in the idea that Turkish Germans, or other people of colour with or without German citizenship, are particularly prone to committing homophobic violence.1 She historicizes the failure of activists to recognize “the exclusionary underpinnings of queer entry into polite society through the politics of commemoration” (p. 181). Here, race and racism, but also class and economic disparities matter. Living and working in the UK, Evans’ insights reminded me of the politics, since 2021, of an image of Alan Turing gracing the British £50 note.2

In developing her approach to kinship, Evans has engaged with a diverse and extremely wide-ranging body of work (here, Elizabeth Freeman, Sara Ahmed, Wendy Brown, Fatima El-Tayeb and Jin Haritaworn feature prominently). Evans’ citational practice (and the gracious acknowledgements) reveals her debt to scholars and activists working in many different interconnected fields. To be sure, Evans’ work has always struck me as profoundly interdisciplinary, but The Queer Art of History pushes these expectations further. In particular, Evans encourages us to look and to hear; the queer art of history has to move beyond the textual, narrowly defined. Evans has collaborated with audiovisual artist Benny Nemer, whose audio guides offer us a fresh perspective on cruising.3 His 2011 remake of the concluding scene of Rosa von Praunheim’s 1971 film, It is Not the Homosexual who is Perverse, but the Situation in which he lives, graces the front cover of the book. These sensory dimensions allow us to think more expansively about the spaces in which kinship is done; Evans places the focus not on what one is, but on what kinship does. One doesn’t simply have, or enjoy, kinship; kinship is made and remade, in spaces such as city streets, cruising grounds, cabaret bars, living rooms, universities, or the Sonntagsclub in East Berlin, formed in the 1980s and still going today, a particularly vital “touchstone” for queer and trans* kinship (p. 133).

Evans particularly focuses on those “folks denied the bonds of lineage” (p. 6). In my own work, I’ve found “affiliative” rather than “biological” bonds the more promising to explore. However, I would like to emphasize that Evans’ reading of kinship is expansive, transnational and inclusive: inclusive also of those “biological” familial links. In chapter three, I was touched by Evans’ reminder that Fritz Kitzing, when persecuted by the Gestapo for cross-dressing and solicitation, was not left in the lurch by his relatives, or at least not by his brother, Hans Joachim. He offered his support and wrote to Kitzing, “I remain eternally grateful for all the love you’ve given me” (p. 97). Until now, historians have not known what happened to Kitzing following his repeated arrests. But as a result of Evans’ book (and the platform of Google Books), a relative in Costa Rica stumbled across a reference to their great-granduncle. They reached out to Evans, saying that Fritz Kitzing survived the Third Reich and worked in an antiques shop, and that they had visited him after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.4 This interaction might itself be seen as queer kinship in action.

The above might suggest my, or our, penchant for a happy ending. There is indeed joy and pleasure in Evans’ book. Equally, Evans does not bury difficult and bruising encounters; hers is no carefree kinship. Yes, Evans asserts the power of solidarity—in one place, she defines kinship as “together-in-difference,” and especially looks at “charged moments of shared struggle” (p. 185; p. 217). But, she is clear-eyed about the racism that has often accompanied queer organising attempts. She also asks us what is lost when we insist on orientating our accounts around ostensible turning-points—the fall of the Third Reich in 1945, homosexual law reform in 1969, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989—which were certainly not turning-points for all concerned. We must not forget “the struggle, losses, inequalities, and compromises that continued to mark queer life after decriminalization” (p. 185).

Craig Griffiths is a Senior Lecturer in Modern History at Manchester Metropolitan University

Notes

- On this topic, see forthcoming Christopher Ewing, The Color of Desire: The Queer Politics of Race in the Federal Republic of Germany after 1970 (Cornell University Press 2024)..

- Turing, who helped crack the Enigma code during the Second World War, was prosecuted for homosexual offences in 1952. He underwent chemical castration as an alternative to imprisonment; he died two years later. He was posthumously “pardoned” by the Queen in 2013. The £50 note is a banknote rarely seen or used by most of the British public.

- Benny Nemer, I Don’t Know Where Paradise Is <https://nemer.be/Paradise> (accessed 4 September 2023).

- See the following thread on Jennifer Evans’ Twitter account: <https://twitter.com/JenniferVEvans/status/1655530959339397124> (accessed 4 September 2023).

Leave a Reply