When I was asked whether I could contribute to this blog series, I immediately jumped at the occasion. It was in the early days of the war in Ukraine, a massive displacement crisis had already commenced, and my social media timeline was filled with calls and responses to aid Ukraine’s refugees stranded on the borders of their country’s neighbors. I am a historian of aid and of migration. I felt like I had a lot to say. Or so I thought. Over a month since the start of the war, and countless news cycles later, I felt like I had, in fact, very little to say. I have struggled with seeing the types of confessions that I had read from Galician or Italian refugees of the First World War almost transplanted to the voices of Ukrainian women and children who fled Russia’s invasion. I struggled with coming to terms with the necessary desensitization regarding narratives of humanitarianism in the first half of the twentieth century as I reacted rather emotionally to current mobilization of resources to help Ukraine’s war sufferers. The blog below is an attempt to, at least partially, overcome these struggles.

This post is a compilation of early reflections on the workings of refugee-centered humanitarian aid. It is the result of my scholarship and my thinking as a historian of humanitarianism. However, it gives little space to how I feel on a purely human level. I was born and raised in Romania; however, I have never been to Ukraine. Still, perhaps perversely, this war has triggered many, often inherited, traumas of people who have lived in so-called “Eastern Europe.” I am one of these people, as I think of my great grandmother, who was a young widow of the Second World War and who was forced to live through the wartime presence of both German and Russian armies in her village of Eastern Romania. I am devastated for the people of Ukraine. I am devastated for the over 10 million children who have been displaced and whose identity will forever be attached to this war. For now, I can only write about those who, for better or worse, mobilized resources to aid them. But it is my hope that these children’s voices will never be lost.

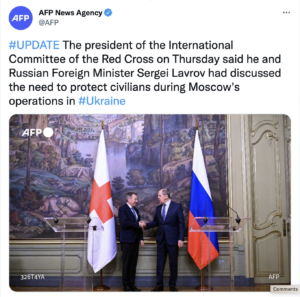

A few days before I started writing this essay a photo of the International Committee of the Red Cross’s (ICRC) president, Peter Maurer, and Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergey Lavrov, made the media rounds. Formally, the ICRC presented this as proof of the organization’s efforts to sustain humanitarian work in Ukraine, in collaboration with all parties. In the following days after this photo, ICRC’s Twitter account presented a series of benefits of its neutrality. “We speak to all sides” was the core message. This was an intrinsic explanation for Maurer’s and Lavrov’s photo-op. It also highlighted, once again, the apolitical principles that international humanitarian organizations have claimed as key to the successful functioning of their work. For many, the Maurer-Lavrov photo-op fell flat, with some questioning the ethics of ICRC’s neutrality in every armed conflict. Still, Maurer’s and Lavrov’s photo-op juxtaposed the recurrent and the rather central narratives of aid for Ukraine’s refugees, focused on the local, community- and volunteer-driven humanitarian work.

The emergence of the plethora of institutions (international organizations and non-governmental organizations, respectively) designed to help those in need (i.e. refugees, war sufferers, hunger victims etc.) after the Second World War has shaped perceptions of humanitarianism as formal and institutional. In my view, this is just one type of humanitarianism. The world and the era I have studied so far are those of the First World War and its aftermath; it was a world of destruction and reconstruction, which, in turn, enabled the emergence of civilian-focused institutional organization for relief. In that world and in that moment, local administrators, volunteers, or ad-hoc emergence of community-based associations to help were also at the forefront of relief work. Generally, I do not encourage direct comparisons and artificial overlapping of different historical moments. For certain, the First World War moment and the relief workings of the time was vastly different than what we see now. However, as Ukraine’s displacement crisis unfolds, the locality and informality of aid have arguably taken center stage yet again.

Scholars of humanitarianism have already observed and written various think-pieces on the relief landscape that Ukraine’s war and the on-going refugee flow have generated. The primary story of refugee aid in this case is one that is driven by individuals, mostly volunteers, local non-profits, or communities in Ukraine’s neighboring countries. Stories of hosted refugees in Romanian or Polish homes or of open borders and welcomed reception in Republic of Moldova, Europe’s poorest country, have made headlines in traditional and social media. Charity concerts and TV programs, online funding campaigns, and other public fundraising schemes have further defined humanitarian mobilization in various European countries. In these narratives of relief, refugees are not mere statistics; they have a voice and a face. Likewise, aid givers are not just mere institutions; they are individuals, communities, “friends” and neighbors. This performed solidarity is not one in reaction to “distant suffering,” as French sociologist Luc Boltanski famously framed it. Rather, it is close and it is deeply personal; it is not apolitical, but rather driven by a seeming “common enemy” and a claimed shared historical experience.

Outside the imagery and narratives of goodwill, I question the future practicality of this locally-driven form of refugee aid. At first glance, this aid is effective; for sure, scholars who will study this communitarian mobilization will draw stronger conclusions in the future. However, as the war continues, the capacity of this localized response to aid remains small scale and indirectly proportionate with the numbers of displaced people who need help. A few days into the war my colleague Olga Byrska volunteered at the border between Poland and Ukraine. In a Twitter post, she wrote of her experience: “We need professional relief systems.” This was a volunteer’s perspective which bluntly reflected on the limits of this rather ad-hoc impromptu mobilization to help Ukraine’s refugees. Indeed, for the first few weeks of the refugee flow, the role of states remained obscure. This is the case in Romania, where individuals, non-profits, local administrations, as well as local communities have represented the first tier “actors” of relief. In the meantime, various international non-governmental organizations and agencies such as UNICEF, UNAIDS, or UNHCR arrived with some professional support. It is possible to think that, in the long run, these organizations will take the reins of refugee aid. However, for the time being, there is little clarity on the potential symbiosis between local, state-driven, and international assistance mechanisms.

The current face of humanitarian aid should also be put in relation to the refugees’ seeming temporary stays. Some critical voices have already pointed out to the selective nature of the response to Ukraine’s refugees in its neighboring countries when compared to discourse, politics, and policies regarding refugees from the Middle East and North Africa. Ukraine’s refugees were welcomed with flowers and piano concerts and food. The other non-European refugees were placed in subpar tents in makeshift camps on European borders. It is difficult to turn a blind eye to these critics and not to acknowledge this selectivity in providing relief. However, I question whether the enthusiastic discourse and actions surrounding help for Ukraine’s refugees will remain the same as the war continues, when their temporary stay becomes permanent, or when various election cycles hit the internal politics across central and eastern Europe. Take for instance the high poverty in some of the main recipient countries; the massive refugee flows pressure state capacity. While the EU promised funds to support these states, regardless of their membership status (e.g. Republic of Moldova), societal frictions and refugees’ “othering” surrounding access to relatively scarce resources are, in my view, potential scenarios once the temporary nature of displacement turns into a permanent stay.

The previous thoughts are merely a few initial reflections on what we have observed in the past few weeks. Generally, for the time being, I remain cautious in rigidly labeling the type of aid that has been circulating in various countries of refugee reception over the past few weeks. In practice, this remains a feeble and fluid situation regarding aid capacity, involved actors, and what could and should happen in relief work as displacement continues. Without a doubt, for the months and years to come, scholars of humanitarianism will scrutinize the many shifts and turns of the relief landscape in Europe in relation to the war in Ukraine and the related refugee crisis. However, it remains to be seen whether these will be the stories of success that the current narratives surrounding refugee aid seem to contour.

Leave a Reply